Urmika Banerjee | Spring 2025

Economic development and global carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions have long been closely related, with urbanization and industrialization fueling increases in energy use and emissions. The energy sector’s CO₂ emissions in 2022 hit a record high of 37 billion tonnes (Gt), a 1% increase above pre-pandemic levels (International Energy Agency, 2023). Resuming economic activity, rising energy demand, and many economies’ continued reliance on fossil fuels are all contributing factors.

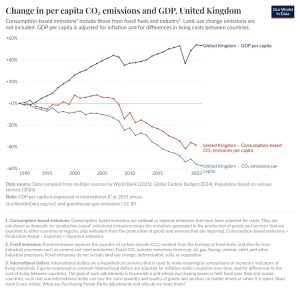

In 2023, however, developed economies experienced a notable shift: emissions fell by 4.5% (520 million tonnes) even as global GDP grew by 1.7% (World Carbon Project, 2023). This decline, bringing emissions back to early 1970s levels, marks the largest non-recessionary drop and signals a significant structural shift away from carbon-intensive energy sources.

The Concept of “The Great Decoupling”

While “The Great Decoupling” traditionally refers to the divergence between productivity, wages, and GDP growth since the 1970s, this paper adapts the term to describe the growing separation between economic growth and carbon emissions a vital shift shaping the future of global sustainability.

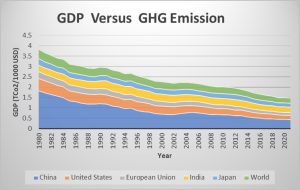

Despite this progress, China’s emissions surged by 565 Mt in 2023, driven by its post-pandemic economic expansion. Still, China leads globally in clean energy investments, responsible for over half of all new renewable capacity added in 2022 (IRENA, 2023). A weak hydropower year contributed to roughly one-third of China’s emissions growth, and its per capita emissions now exceed those of advanced economies by 15%.

India, fueled by a strong 6.3% GDP growth, saw an increase of nearly 190 Mt of CO₂ emissions (World Bank, 2023), exacerbated by a weak monsoon that reduced hydropower output and increased dependence on fossil fuels.

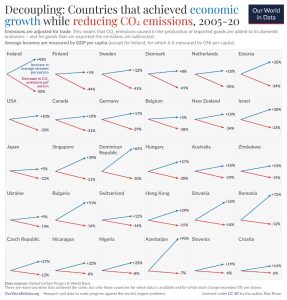

Trends and Analysis

In 2023, global CO₂ emissions grew by only 1.1% substantially lower than the 3% increase in global GDP (World Bank, 2023). This shift indicates a break from the historical pattern where CO₂ emissions mirrored economic growth. According to Our World in Data (2024), many high-income countries, including the US, UK, and EU, have already achieved “absolute decoupling,” where economic growth continues while emissions decline. For example, between 1990 and 2020, the EU reduced emissions by approximately 30% while growing its economy by over 60%. This trend reflects structural shifts toward renewable energy, improved energy efficiency, and a transition to service-based economies.

On a global scale, emissions have grown at just 0.5% annually over the past decade, despite significant GDP growth. Historically, such slowdowns were only seen during global shocks like the Great Depression and World Wars (Carbon Tracker, 2023), but today they signal a sustained decoupling trend driven by technological and structural change.

Policy Implications and Future Outlook

The decoupling is supported by four major pillars:

-

- Shift to Service Economies: Nations like India and China are transitioning to service-dominated economies, with a projected 30% reduction in energy intensity by 2030 (IEA, 2023).

- Enhanced Energy Efficiency: Energy consumption per unit of GDP has decreased by 20% over the past decade due to technological improvements (World Bank, 2023).

- Electrification: Electrification is expected to account for

70% of total energy consumption by 2030, moderating overall energy demand (IRENA, 2023).

- Renewables Expansion: The share of renewables is projected to rise from 15% in 2022 to over 30% by 2030 (IRENA, 2023), driven by falling c

osts and accelerated adoption.

Our World in Data highlights that while several advanced economies have already decoupled, emerging economies still face the dual challenge of sustaining economic growth while reducing emissions. Bridging this gap will require not only technological diffusion but also ambitious policies.

Conclusion

The emerging decoupling of CO₂ emissions from economic growth represents a fundamental shift in the global energy landscape. While advanced economies demonstrate that emissions reductions and growth are not mutually exclusive, countries like China and India still face structural hurdles. Continued innovation, investment in renewables, and region-specific policy interventions will be crucial to achieving global decoupling and building a resilient, sustainable future.

————

Ritchie, H. (2021, December 1). Many countries have decoupled economic growth from CO2 emissions, even if we take offshored production into account. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/co2-gdp-decoupling

The great decoupling – economist’s view – typepad. (n.d.). https://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2011/02/the-great-decoupling.html

IEA. CO₂ Emissions in 2022 – Analysis. Paris: International Energy Agency, 2023. https://www.iea.org/reports/co2-emissions-in-2022..

Ritchie, Hannah, Pablo Rosado, and Max Roser. “CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions.” Our World in Data, December 5, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions.

IEA. World Energy Outlook 2023 – Analysis. Paris: International Energy Agency, 2023. https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2023.

“World Energy Transitions Outlook 2023: 1.5°C Pathway.” IRENA, June 1, 2023. https://www.irena.org/publications/2023/Jun/World-Energy-Transitions-Outlook-2023.

“World Development Indicators.” DataBank. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

“Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions Increase Again in 2024.” ScienceDaily, November 12, 2024. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2024/11/241112191227.htm.