Online Journal | Matthew Hummell | February 2026

There is nothing more economically gratifying for a town than its own development. When the prospect of growth comes knocking at that “welcome” sign, municipalities understandably leap at the chance. Newspapers and political networks celebrate revitalized downtowns and rising property values, but beneath the balloons floating at ribbon cuttings and the glamorous headlines plastered across bus stops lies a quieter and more complex fiscal tradeoff. The same tax incentives used to attract development, often structured as Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILOTs), influence how public revenues are distributed, including the flow of funds to local public schools.

As a result, PILOTs shape municipal budgets and the allocation of the taxpayer dollar within New Jersey’s public school funding system. At first glance, these agreements appear to be a financial win, as they support development that might not otherwise occur. Over time, their broader impact affects how local growth aligns with statewide approaches to education funding.

Under a PILOT, a developer agrees to make an annual payment to the municipality instead of paying traditional property taxes. The idea is to encourage investment in underdeveloped areas by lowering tax burdens. That appears to be a wonderful economic opportunity. However, the caveat is understanding where those tax payments go. Unlike standard property taxes, which apply a weighted split of revenue for the counties, municipalities, and schools, PILOT revenues flow almost entirely to municipalities. School districts and counties are overlooked entirely. According to the New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, municipalities can retain up to 95% of PILOT proceeds, leaving only 5% for counties, and nothing for schools.

This structure creates strong financial incentives for towns and cities to approve PILOTs even when they undercut local schools. From their perspective, they are getting something when they otherwise would have gotten nothing. For mayors and councils, PILOTs look like “easy money,” a steady stream of revenue that they can control directly. For developers, long-term tax liabilities are reduced while still receiving the full economic payoffs of the development. But for schools, this becomes a slow and painful funding squeeze. A growing share of a community’s wealth becomes locked away from schools.

The fiscal consequences become obvious once development breaks ground. When a city approves a PILOT for an apartment tower, office park, or retail center, the assessed value of that property is removed from the school tax base for, typically, 20-30 years. Schools receive none of the revenue generated by the project, even as the same development increases student enrollment and thus the need for teachers, counselors, and other essential services. Municipalities enjoy an increase in the taxable value of property. Developers enjoy reduced taxes on their developments. While Instagram posts may look better with a nicer skyline, schools are left with the same budgets and a lot more children running around the halls.

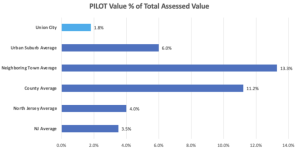

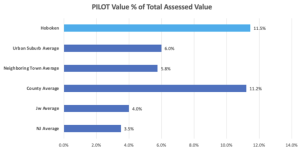

This disconnect is especially visible when comparing municipalities that rely heavily on PILOTs with those that do not. In Hoboken (2025), where luxury and mixed-use developments are frequently placed under PILOT agreements, more than 11 percent of the city’s total assessed property value is tied up in PILOT-exempt properties, which is over three times the statewide average. By contrast, neighboring Union City (2025), which has far fewer PILOT agreements, has only about 2 percent of its assessed value under PILOT status, allowing most new development to remain within the traditional school tax base. As a result, increases in property values in Union City more directly translate into additional revenue for local schools. Together, these cases illustrate how the use of PILOTs can weaken the connection between local economic growth and school funding.

PILOT value as a percentage of total assessed property value in Union City (Top) and Hoboken (Down), shown alongside selected local and statewide benchmarks.

PILOT value as a percentage of total assessed property value in Union City (Top) and Hoboken (Down), shown alongside selected local and statewide benchmarks.

Source: New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, PILOT Database and Viewer (Municipal Tax Abatement Toolkit).

Yet the most consequential effects occur at the state level. Under the School Funding Reform Act (SFRA), New Jersey determines each district’s “local fair share” using equalized property values, not actual taxable property available to schools. Equalized property value reflects the true market value of all taxable property in a town after adjusting for local assessment differences. PILOT properties count as local wealth that schools cannot access. On paper, municipalities appear able to support their schools. In practice, they contribute far less than the formula anticipates because their most valuable developments are exempt.

To prevent sudden disruptions in school funding, the state responds by adjusting aid allocations under the School Funding Reform Act. This dynamic can be observed in municipalities such as Hoboken, where redevelopment has occurred under PILOT arrangements while state aid formulas continue to rely on equalized property values. Because state education aid is allocated from a finite funding pool, these adjustments have a broader impact on how resources are distributed across districts statewide.

The long-term cost is a quiet erosion of statewide equity. Districts unable to depend on rising taxable property values face deferred maintenance, larger class sizes, and fewer student supports. Even when state aid prevents full funding cuts, these schools lose the stability and growth opportunities that normally accompany local economic growth. Meanwhile, municipalities keep 95% of PILOT revenues, keep property taxes low, and continue approving PILOT redevelopment.

PILOTs are a flexible policy instrument when analyzed within their broader fiscal and regulatory context. They serve municipal development objectives while granting favorable conditions for private investment and modifying the flow of funds within New Jersey’s school funding system. Their overarching impact differs from municipality to municipality, as determined by the local economic climate, enrollment patterns, state aid formulas, and the specific terms of each agreement. If entrusted to professionals who understand both the costs and benefits of PILOTs, this tool can be extremely valuable in the overall economic development of an area.

[1] New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, Division of Local Government Services, Local Finance Notice 2025-12, 2025, www.nj.gov/dca/dlgs/lfns/2025/2025-12.pdf

[2] New Jersey School Boards Association, Understanding New Jersey School State Aid Funding, 2024, www.njsba.org/school-leader/school-leader-summer-2024/understanding-new-jersey-school-state-aid-funding

[3] New Jersey Department of Education, School State Aid Overview, www.nj.gov/education/stateaid/

Sources

New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. PILOT Database and Viewer. Municipal Tax Abatement Toolkit, www.nj.gov/dca/divisions/dlgs/programs/pilot.shtml.

New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. Division of Local Government Services. Local Finance Notice 2025-12. 2025, www.nj.gov/dca/dlgs/lfns/2025/2025-12.pdf.

New Jersey Department of Education. School State Aid Overview, www.nj.gov/education/stateaid/.

New Jersey School Boards Association. Understanding New Jersey School State Aid Funding. 2024, www.njsba.org/school-leader/school-leader-summer-2024/understanding-new-jersey-school-state-aid-funding.